Workers bear 71% to 100% of the cost of increases in compulsory super

Robert Breunig,Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National UniversityandKristen Sobeck,Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

The government’s much-anticipated Retirement Incomes Review has found that increases in employer’s compulsory superannuation contributions are financed by reductions in workers’ wage growth.

This isn’t obvious, and it certainly isn’t what the superannuation industry has been saying.

Legally, those contributions (at present 9.5% of each wage) come from employers, on top of the wage.

Employers are required to pay them under a legal instrument known as the “superannuation guarantee”.

But employers have to get the money from somewhere.

Compulsory super was introduced in 1992 with the intention the money would come out of funds that would otherwise have been used for wage increases. The document said workers would be

forgoing a faster increase in real take-home pay in return for a higher standard of living in retirement

Government ministers encouraged employers to shave wage increases to pay for increases in compulsory super. In 2012 then minister Bill Shorten explained:

a portion of what would have been employees’ increases will go into compulsory savings

Modelling by the Treasury, Reserve Bank, Grattan Institute, and the private sector has long assumed that is what happens.

Then in February groundbreaking research by the Grattan Institute on 80,000 enterprise bargaining agreements over three decades of compulsory super found that was indeed what has been happening.

Grattan found that on average,80%of each increase in compulsory super has been taken from what would otherwise have been a wage increase.

And now, in work commissioned by the Retirement Incomes Review using completely different data (from the Tax Office instead of enterprise agreements) and an entirely different analytical approach, so have we.

Here’s what we did

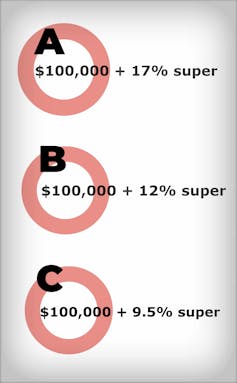

Imagine three companies (A, B, and C) offering an identical job in the same city with three different annual total compensation packages: $117,000 (A), $112,000 (B), and $109,500 (C).

The three companies offer the same wage ($100,000), they only differ in the amount of super they pay their workers: 17% (A), 12% (B) and the legally-required 9.5% (C). In this example, total compensation equals wages plus superannuation.

In a competitive labour market (which we largely have in Australia), job seekers would flock to company A, which offers the best compensation package.

How might B and C respond to get workers back?

By offering higher wage growth in subsequent years than A. Higher wage growth would ultimately lead to a catch-up in total compensation levels across the three firms, over time.

Examining the administrative tax records since compulsory super has been set at a single standard rate, that is indeed what we found – when a firm paid super at more than the standard rate, those firms that paid less or merely the standard rate lifted wages by more.

Put another way, the firms that paid their workers more than the legislated rate of super lifted their wages by less.

What happens when compulsory super is increased?

Legislated increases to the standard rate of compulsory super increase firms’ labour costs, but only for firms that pay the standard rate (in our example that’s firm C which we will call a super guarantee “SG” firm).

By comparing the difference in wage growth of employees in “SG firms” to “above SG” firms (companies A and B) during periods when the minimum super guarantee was increased, we can determine how companies pay for the increase in labour costs.

We already know that wage growth for “SG firms” is higher than “above SG” firms.

The question is: how does that change when the SG increases?

If “SG firms” find the money to fund the higher SG from somewhere other than wages, it won’t change at all.

If they pass on some or all of the cost to their workers in lower wage increases, then their wage growth should slow relative to that of “above SG” firms.

Our examination of Tax Office data finds this is what has happened.

Our results show that when the legislated compulsory super contributions increased from 8% to 9% in 2002 and again from 9% to 9.25% in 2013, companies passed on 71% to 100% of the cost to workers in the form of reduced wage growth.

What about other findings?

Two other studies, one funded by Industry Super, do not find a trade-off between super increases and wage increases (and in some instances present a case for superannuation increases leading to wage increases).

As we are seeing in the current debates about pausing increases in compulsory super, it tends to be politically easy to raise compulsory super when wage growth is robust and convenient to pause increases when wage growth is slow.

The correlations observed in these studies (that wage growth has been high when compulsory super has been increased) may well be picking up on the timing of increases in compulsory super – that they have been introduced at times when wage growth has been strong rather than having caused strong wage growth.

Where does it leave us?

Increases in compulsory super come at a cost to the wages of workers.

They might result in higher retirement incomes later in life (although this is uncertain because the settings of the age pension mean an increased superannuation balance is not directly correlated with an increase in retirement living standards).

But they leave less disposable income available to workers and their families to consume today or to save through alternative means.

They also cost the government money.

An increase in compulsory super contributions might one day reduce age pension expenditure, a question examined by the review.

But in the years before then, the government would forego substantial tax revenue because the extra super would be taxed at a lower rate than wages.

These are important things for the government to consider as it decides whether to proceed with the legislated increase in compulsory super from 9.5% of salary to 12% in five steps of 0.5% between July 2021 and July 2025.![]()

Robert Breunig, Professor of Economics and Director, Tax and Transfer Policy Institute, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University and Kristen Sobeck, Senior Research Officer, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Jobs Just For You, The HR Professional

Our weekly or daily email bulletins are guaranteed to contain only fresh employment opportunities

Latest Jobs

Learning and Development Team Leader

Victoria

Recruitment Coordinator - Contract

Western Australia

Recruitment Officer

Western Australia

WHS Business Partner

New South Wales

Senior People Partner (Temp – Up to 6 Months)

New South Wales

HR Manager - Construction Project - Contract

South Australia

HR Business Partner

Western Australia

HR Advisor - Contract

Victoria

Senior HR Manager

New South Wales

HRBP - Contract

New South Wales

HR Business Partner - Contract

Victoria

HR Advisor - Contract

South Australia

QHSE Coordinator

Queensland

Recruitment Advisor - Contract

Western Australia

Senior HR Business Partner - Contract

Western Australia

Learning & Development Specialist - Contract

Western Australia

HR Generalist - Contract

Western Australia

Talent Acquisition Advisor - Contract

Victoria

HR Business Partner - Contract

Victoria

HRBP - Contract

New South Wales

Senior Workplace Relations Advisor - Contract

New South Wales

HR Manager

Western Australia

Senior Manager Industrial Relations - Contract

New South Wales

Senior HR and Safety Advisor - Contract

Tasmania

HR Business Partner

New South Wales

Talent Acquisition Partner - Contract

Victoria

HR Advisor

Western Australia

HR Advisor

Victoria

HR Manager

Western Australia

HR Business Partner

Western Australia

HR Advisor - Contract

Victoria

Manager, Human Resource Services

Queensland

HR Advisor - Contract

Western Australia

HR Advisor - Contract

Western Australia

HR Manager - Construction Project - Contract

South Australia

HR Coordinator

New South Wales

HR Business Partner

Western Australia

HR Advisor

Western Australia

Employee Relations Advisor - Contract

Victoria

Instructional Designer - Contract

New South Wales

HR Business Partner

Victoria

Senior HR Business Partner

Western Australia